There is a particular kind of dread that creeps in when a tool you’ve trusted for years suddenly betrays you. That was my experience with my Datacolor Spyder5, a device whose name now feels unintentionally prophetic. One morning it simply stopped working, as if it had curled up its legs and died.

For years, my dependable calibration tool has been a Datacolor Spyder5. It was never a device I felt strongly about, but it was familiar and widely used. It promised convenience. You plug it in, run the software, and trust that the colours on your screen are now accurate.

Last week, I pulled my pet Spyder off the shelf to calibrate my monitors, having left them to their own devices for far too long, to find that it had simply stopped working. As such, I opened Device Manager to see what the system thought it was seeing.

Initially, the Spyder5 did appear in Device Manager, but not as a Datacolor device. The Hardware ID was malformed, missing the expected VID_085C signature. Instead of identifying itself as a colorimeter, it showed up as a generic USB device with no class, no vendor, and no usable driver association. That confirmed the firmware had lost its ability to announce what the device actually was. There was no recovery mode, no fallback driver, and no way to reflash it. This morning I plugged it back in to get a screenshot of the reported harware ID, but it is now altogether missing from the Device Manager – all eight legs now pointing skywards! It was a reminder that this was not really an instrument to be relied upon in the traditional sense. It was a small consumer device with a fragile internal architecture, and once that architecture failed, the entire tool was lost. Not an insignificant loss either with the Spyder 5 Studio kit costing upwards of £250 when new.

That failure forced me to reconsider my approach to colour management. I rely on accurate colour for my work. I need a calibration device that I can rely on rather than a consumer gadget. I need something that will remain stable for years, not something that might randomly drift or die just because a vendor has moved on to the next product cycle.

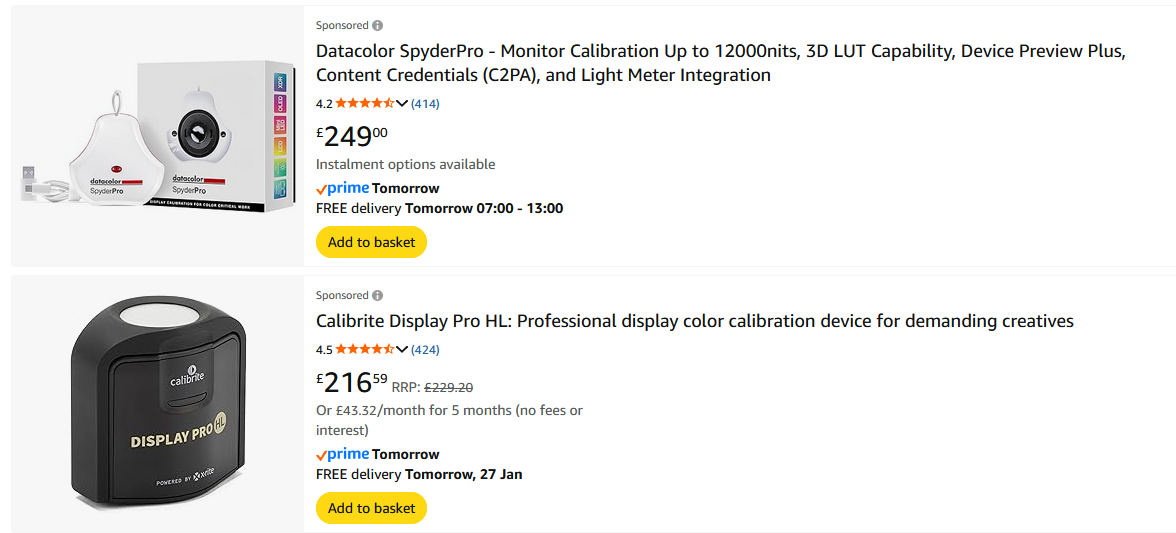

So now it’s time to reinvest in a new colorimeter, and the process of choosing one revealed a great deal about the differences between consumer‑grade devices and instrument‑grade tools. The journey eventually brought me to the X‑Rite and Calibrite colorimeters. What I learned along the way is worth sharing, because it clarifies a topic that is often clouded by marketing and misunderstanding.

After spending a few evenings researching the failure of my Spyder5, I discovered that mine was not an isolated incident. There are several reports of firmware corruption in the Spyder 5 devices, generally after they have not been used for an extended period, where the internal controller loses part or all of its firmware program if it is not rewritten through regular power cycles of the device. Over and above this, it also highlighted a deeper issue with the class of devices it belongs to. Many consumer‑level colorimeters rely on organic dye filters. These filters are essentially coloured plastics placed in front of the photodiodes. They are vulnerable to fading, yellowing, moisture absorption, and chemical ageing. Because a colorimeter’s accuracy depends entirely on the stability of those organic compounds, any change in the dyes over time becomes a change in the measurements.

There is little to no teardown information out there on the Spyder 5 colorimeter, so I thought it appropriate to document it here:

At first I tried to pry apart the upper and lower shells of the device – presuming that there would be some clips that I’d likely break in the process, but it soon became evident that it was held together some other way.

After prying up the “Spyder5” sticker, I found two 1.3mm hex-head screws, which, when removed allowed me to lift off the top cover without any clips to damage.

This revealed three more 1.3mm hex-head screws and an electrical connector.

After removing the three scerws, the electronic board could be lifted away revealing the array of photodiodes and dye-based filters.

Inside the Spyder5, I found a Silicon Labs F327 microcontroller. which is a flash-based chip with no hardware-level protection. Its firmware, USB identity, and calibration data all live in the same rewritable memory block. Such flash devices are fine if used regularly, as the firmware itself will usually “refresh” on each power-up, but if left on the shelf for a long period, the charge in the flash based memory block degrades, and once even just a single “bit” becomes corrupted, the device loses its ability to enumerate, loses its calibration, and more importantly loses its own ability to “survive”, becoming unrecoverable.

So having found the likely culprit for the failure of my own device, I have also broken down the optical stack, for the sake of completeness.

It includes, from innermost to outermost: (top to bottom, left to right)

Seven-element filter array (six plus one open pass-through – likely for measuring luminance)

Spacer

Fresnel Lens

Spacer

Composite glass and white plastic diffuser

30-degree optical honeycomb grid

This explains why older Spyder units often produce inconsistent results. The hardware itself is inherently unstable. The filters drift. The spectral response shifts over time. The device becomes less reliable with every passing year – even moreso if it sits on the shelf for extended periods. Many users have reported devices that suddenly stop being recognised by the software or the operating system. The failure I experienced is not unique. It is a known weakness of the platform. Most photographers never realise this. They assume their calibration device is a scientific instrument. They assume it is precise and stable. In reality, many of these devices are built to meet a price point rather than a standard. They are designed for the mass market, not for long‑term reliability.

The Spyder5’s successor, “Spyder X” does apparently address the optical degradation noted above by using interference filters rather than dye-based filters, but the device is still very much a consumer-grade trinket – depite it’s significant price point – containing lightweight microcontrollers and fragile memory. Once you understand this, the appeal of the i1Display Pro becomes clear.

The i1Display Pro and its Calibrite successors use a completely different approach to colour measurement. Instead of organic dyes, they use interference filters. These are thin‑film optical coatings made of metal oxides. They do not fade or yellow. They do not absorb moisture. They do not drift with UV exposure. They behave like tiny optical mirrors that split light in a stable, repeatable way.

This technology is used in scientific instruments, industrial colour measurement systems, and high‑end spectrophotometers. It allows an i1Display Pro from 2014 to remain just as accurate in 2026.

I found a teardown of the I1 Display Pro online, showing its use of the bulletproof Microchip PIC18F family of MCUs. These are industrial grade components commonly used in harsh environments. We use this family of microcontrollers in oilfield applications, in environments from the Arabian Desert to Alaska. The 24LC641 is an industrial EEPROM, indicating that the main controller firmware is held in the PIC18F’s robust memory, while calibration information is held in the EEPROM flash. Both will likely remain stable for decades.

One source of confusion in recent years has been the rebranding of X‑Rite’s photographic division to Calibrite. This has led many people to assume that the Calibrite ColorChecker Display Pro is a newer or more advanced device than the older X‑Rite i1Display Pro – This is not the case: The hardware is the same. The filters are the same. The sensors are the same. The internal electronics are the same. The only differences are the casing, the logo, and the software ecosystem.

This means that buying a used i1Display Pro from 2018 or 2019 is not a compromise. It is the same instrument you would receive if you purchased a brand‑new Calibrite unit today, and without any significant opportunities for degradation, it seems that buying a used i1 Display-pro is the most sensible option.

Because I use DisplayCal and ArgyllCMS, I am not paying for vendor software anyway. I am paying for the hardware. The stable, interference‑filter hardware that actually matters.

When I began researching, I assumed that older units would be less desirable. Electronics age. Components degrade. Plastics become brittle. Capacitors dry out. That is the usual story.

The i1Display Pro is not a typical electronic device. It is a sealed optical instrument with no consumables, no high‑stress components, and no organic materials in the optical path. The parts that determine accuracy, such as the filters and photodiodes, are effectively immune to the kinds of ageing that affect cheaper devices.

This is why colour‑management technicians routinely use i1Display Pros that are more than a decade old. They verify them against reference spectrophotometers and find them still within tolerance. It is also why the design has remained unchanged for so long. It did not need to evolve. It was already stable.

A 2014 i1Display Pro will last just as long as a 2025 Calibrite ColorChecker Display Pro. The manufacturing date is not a meaningful factor. The engineering is what matters.

I don’t want a workflow that depends on luck or on the goodwill of a manufacturer. I want a workflow that behaves like a well‑designed mechanical tool. It should be predictable, stable, and trustworthy. The failure of the Spyder5 was a reminder that the invisible parts of the craft deserve just as much care as the visible ones.

The i1Display Pro doesn’t need to be exciting. It is just a reliable instrument that performs its task without fuss. In a world full of disposable technology, that feels pretty radical.